Addressing Maxillary Hypoplasia During Growth—A Paradigm Shift?

BY SABINE GIROD

You changed my life!” – is the sentence we as OMF surgeons hear most often from our young adult patients. Orthognathic surgery changes lives, but too late? Due to the current paradigm orthognathic surgery can only be performed once craniofacial skeletal growth is completed. Thus, a child must wait and cope with a sometimes-disfiguring facial deformity or treatment which in many cases has significant negative psychosocial impact during adolescence.

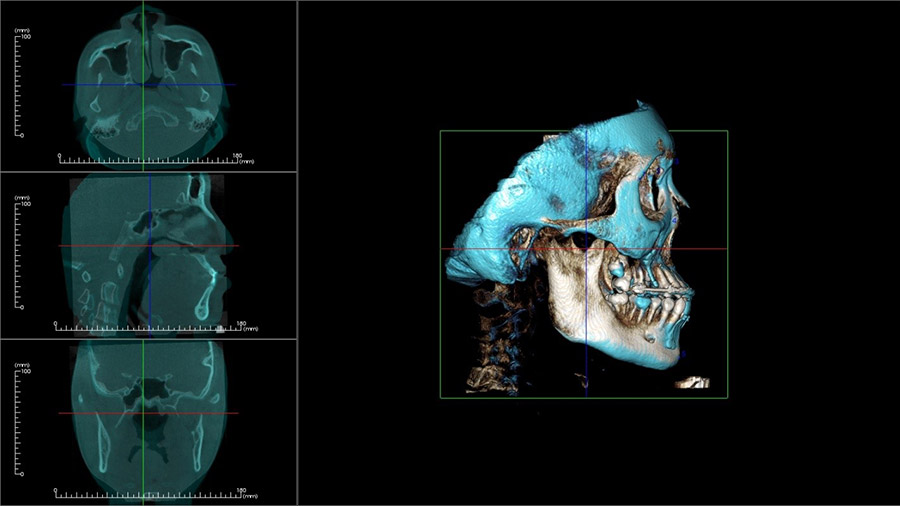

There are new techniques for patients with maxillary hypoplasia – many of them with cleft lip and palate who develop severe facial concavity and a class III malocclusion due to growth restriction in the maxilla resulting from soft tissue scarring. These occlusions require intensive orthodontic treatment for functional and esthetic improvement during the growth period, often in conjunction with orthognathic surgery later.

In the 1970s, Delaire introduced the early orthodontic treatment of maxillary hypoplasia during growth via dentally based maxillary protraction, and this protocol has been successfully employed for the treatment of patients with CLP. However, there are disadvantages of Delaire’s facemask, including low patient compliance due to discomfort, increased facial height due to clockwise rotation of the mandible, and lingual inclination of lower incisors. In addition, long-term follow-up of maxillary protraction shows 25% to 33% relapse of negative overjet after the mandibular growth is finished. In 1997, Polley and Figueroa introduced maxillary distraction osteogenesis with a rigid external distraction (RED) system for patients with CLP and severe maxillary hypoplasia. In this study, the intraoral appliance was normally connected to maxillary teeth, and unfavorable maxillary tooth movement was reported. To prevent these unwanted dental changes, Swennen et al. used maxillary distraction osteogenesis with a skeletal anchorage system, combined with fixed miniplates and a rigid external appliance. However, while this method did not require a facemask, it still relied on patient compliance.

In 2009, De Clerck et al. introduced the use of miniplates and maxillomandibular elastics to achieve orthopedic traction of the maxilla, avoiding the need for external appliances such as a facemask or a rigid external appliance. Using this method, patients were required to replace the elastics once per day and maintain good oral hygiene. In addition to this low requirement of patient cooperation, wearing maxillomandibular elastics was reported to be less psychosocially stressful for the patients than wearing a facemask, especially in school-age children.

Continue the discussion:

On February 24, 2022, I will be speaking at the following AO CMF Study Club event:

AO CMF Study Club MENA—MM Distraction during growth

Thursday, February 24 at 17:00 Central European Time

During the one-hour session we will discuss these treatment modalities and suggest a new concept for diagnosis and addressing maxillary hypoplasia in syndromic and non-syndromic children and adults including sleep apnea, maxillary protraction, and orthognathic surgery.

Do you want to know what is the topic of the next study club events? 2022 themes

About the author

Dr. Sabine Girod is Professor emerita of Surgery in the Department of Surgery at Stanford. She trained in Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery in Germany and completed a postdoctoral research fellowship at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (Harvard Medical School) in Boston. Her special clinical and research interests are maxillofacial trauma, corrective surgery of maxillofacial deformities, and minimally invasive Computer Aided Surgery.

She is currently serving as the Chair of the Network Development Commission on the International Board of AO CMF of the AO Foundation in Switzerland, a global nonprofit organization dedicated to improving the care of people with musculoskeletal injuries and deformities. In this role she focuses on creating mobile online access to on demand peer-to-peer consulting and surgical education for surgeons all over the world. Among other projects she co-chairs the development of “AO College”, a modular surgical and professional education program for young surgeons geared at building a global and diverse community of future leaders among the next generation.

References:

- Ross RB. Treatment variables affecting facial growth in complete unilateral cleft lip and palate. Part 6: technique of palate repair. Cleft Palate J 1987;24:5-77

- Delaire J. Manufacture of the ‘‘orthopedic mask’’. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 1971 Jul-Aug;72(5):579-82.

- Hass AJ. Palatal expansion: just the beginning of dentofacial orthopedics. Am J Orthod. 1970;57:219-255.

- Baik HS. Clinical results of the maxillary protraction in Korean children. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1995;108:583-92.

- Kapust AJ, Sinclair PM, Turley PK. Cephalometric effects of face mask/expansion therapy in Class III children: a comparison of three age groups. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998;113:204-12.

- Takada K, Petdachai S, Sakuda M. Changes in dentofacial morphology in skeletal Class III children treated by a modified maxillary protraction headgear and a chin cup: a longitudinal cephalometric appraisal. Eur J Orthod. 1993;15:211-21.

- Baccetti T, McGill JS, Franchi L, McNamara JA Jr, Tollaro I. Skeletal effects of early treatment of Class III malocclusion with maxillary expansion and face-mask therapy. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998;113(3):333-43.

- Wells AP, Sarver DM, Proffit WR. Long-term efficacy of reverse pull headgear therapy. Angle Orthod 2006;76(6):915-22.

- Polley JW, Figueroa AA. Management of severe maxillary deficiency in childhood and adolescence through distraction osteogenesis with an external, adjustable, rigid distraction device. J Craniofac Surg. 1997;8:181-5.

- Figueroa AA, Polley JW. Management of severe cleft maxillary deficiency with distraction osteogenesis: procedure and results. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1999;115:1-12.

- Swennen G, Dujardin T, Goris A, De Mey A, Malevez C. Maxillary distraction osteogenesis: a method with skeletal anchorage. J Craniofac Surg. 2000;11:120-7.

- Hugo J. De Clerck et al. Orthopedic Traction of the Maxilla with Miniplates: A New Perspective for Treatment of Midface Deficiency. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:2123-9.

- Cornelis MA, Tepedino M, Riis NV, Niu X, Cattaneo PM. Treatment effect of bone-anchored maxillary protraction in growing patients compared to controls: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Eur J Orthod. 2020:cjaa016. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjaa016. [Epub ahead of print].

Palikaraki G, Makrygiannakis MA, Zafeiriadis AA, et al. The effect of facemask in patients with unilateral cleft lip and palate: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Orthod. 2020:cjaa027. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjaa027. [Epub ahead of print]. - Heymann GC, Cevidanes L, Cornelis M, De Clerck HJ, Tulloch JF. Three-dimensional analysis of maxillary protraction with intermaxillary elastics to miniplates. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;137(2):274-284.

- De Clerck H, Cevidanes L, Baccetti T. Dentofacial effects of bone-anchored maxillary protraction: a controlled study of consecutively treated Class III patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;138(5):577-581.

- Nguyen T, Cevidanes L, Paniagua B, et al. Use of shape correspondence analysis to quantify skeletal changes associated with bone-anchored Class III correction. Angle Orthod. 2014;84(2):329-336.